Laurent Series

First, some background on geometric series.

The geometric series

$$ \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} ar^n $$

can be written as

$$ \frac{a}{1 - r} $$

and converges for $\|r\| < 1$.

Now, when we have a term like $\frac{1}{z-2}$ we can write

$$ \frac{1}{z -2} = -\frac{1}{2 - z} = - \frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{1 - \frac{z}{2} } = - \frac{1}{2}\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \left ( \frac{z}{2} \right )^n, \tag{a} $$

and we can write

$$ \frac{1}{z - 2} = \frac{1}{z} \cdot \frac{1}{1 - \frac{2}{z}} = \frac{1}{z} \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \left ( \frac{2}{z} \right )^n = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{2^n}{z^{n+1}}. \tag{b} $$

The geometric series from (a) will converge when $z < 2$, and the geometric series from (b) will converge when $z > 2$. So, we have a choice of which geometric series to take, depending on the region of $z$ we want to work in.

Laurent Expansion Theorem. Let $f$ be analytic in an annulus $D : r < \|z - z_0\| < R$. Then $f(z)$ can be expressed in the form

$$ f(z) = \sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} a_n (z - z_0)^n $$

which converges and represents $f(z)$ in $D$.

Note the negative powers of $n$ - this is a distinguishing factor between Laurent series, which only apply to Complex functions and not Real functions, and Taylor series.

Example

We will find the Laurent series for $f(z) = \frac{z}{z^2 - 3z + z}$ for $D : 1 < \| z - 3 \| < 2$.

We can factor the denominator of $f(z)$ to get

$$ f(z) = \frac{z}{z^2 - 3z + z} = \frac{z}{(z - 1)(z - 2)}. $$

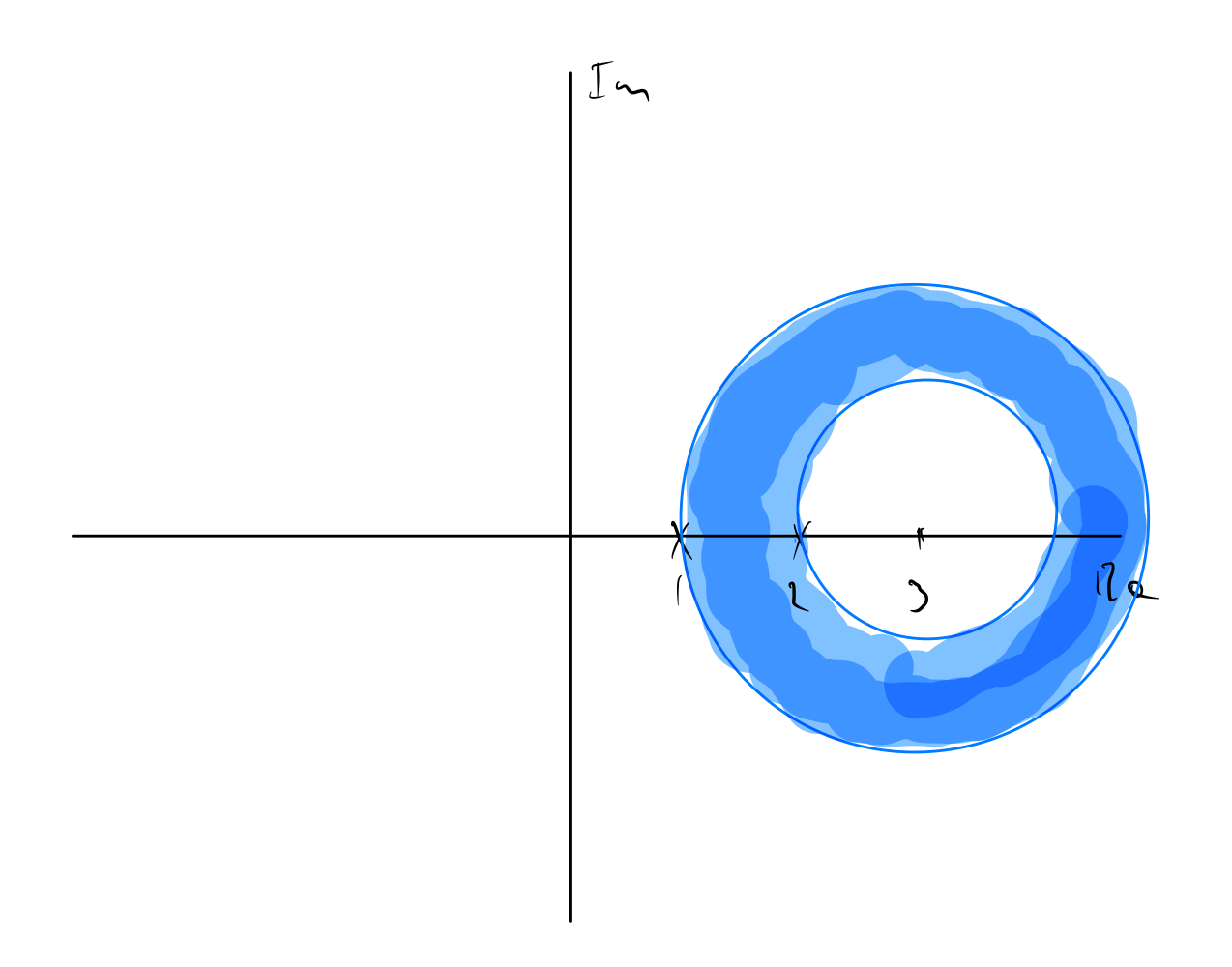

This makes it evident that $f(z)$ has singularities at $z = 1, 2$, and our domain of definition is an annular disc centered at $z = 3$, with an internal disc of radius $1$ and an annulus of width $1$ outside of that:

Now, via partial fraction decomposition we get

$$ \frac{z}{(z - 1)(z - 2)} = \frac{2}{z-2} - \frac{1}{z - 1}. $$

We need to use the two terms above to find geometric series in $(z-3)^n$ that converge for the interior of the annular disc, the region $\|z - 3\| < 1$, and the exterior of the annular disc, the region $\|z - 3\| > 2$.

Starting with the first term, we have

$$ \frac{2}{z-2} = \frac{2}{(z-3) + 1} = \frac{2}{(z - 3)(1 + \frac{1}{z - 3})} = \frac{2}{z-3} = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^n}{(z-3)^n} = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^n}{(z-3)^{n+1}}, $$

which converges for $\|z -3\| > 1$, which includes the region $\|z - 3\| > 2$. Note that this series involves negative integer powers of $(z -3)$ as the $(z - 3)$ term is in the denominator.

With the second term, we have

$$ \frac{-1}{z-1} = \frac{-1}{(z - 3) + 2} = \frac{-1}{2} \left ( \frac{1}{1 + \frac{z - 3}{2}} \right ) = \frac{-1}{2} \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \left ( \frac{-(z - 3)}{2} \right )^n = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^{n+1}}{2^{n+1}}(z -3)^n, $$

which converges for $\|z - 3\| < 2$, which includes the region $\|z - 3\| < 1.$ Note that this series involves positive integer powers of $(z - 3)$.

Combining the two, and adjusting the range of summation for the first series to get a $(z-3)^n$ term rather than $(z -3)^{n+1}$, we can add the two together to get

$$ f(z) = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^{n+1}}{(z-3)^{n}} + \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^{n+1}}{2^{n+1}}(z -3)^n, ~ 1 < |z - 3| < 2. $$

General Method for Finding all Taylor and Laurent Series

If we want to find all of the Taylor and Laurent Series for $f(z)$ centered at $z_0$ we can do this:

1. Consider where there are singularities.

If the is a disc around the center that contains no singularities, then we'll have a taylor series centered at that disc, and its region of convergence will extend until the first singularity is encountered.

If there is an isolated singularity at the center, then we'll only have Laurent series.

If there is an isolated singularity other than at the origin, then we may have a Taylor (or Laurent) series that's convergent around the origin, and then another Laurent series on the outside of that singularity.

It helps to draw these singularities and regions out - we need to find series to cover all of them.

2. Make a substitution to $w$ land

We let $w = z - z_0, z = w + z_0.$ This translates us to being centered at $z_0,$ which makes it easier to do algebraic manipulation.

3. Deal with each region

We write a series for each region by writing it as a binomial series, potentially multiplied by analytic factors.

For a Binomial Series, we have

$$ (1 + x)^{\alpha} = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\binom{\alpha}{n}x^n, |x| < 1. $$

So, we need to do something to make $|x|$ small. As an example, if we have

$$ \frac{1}{(w+i)^{2}}, $$

We can factor out $i$ from the denominator to get

$$ \frac{1}{(i(1+\frac{w}{i}))^2} = \frac{-1}{(1+\frac{w}{i})^2} = - \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \binom{-2}{n} \left ( \frac{w}{i} \right )^n, $$

where $|\frac{w}{i}| < 1$ when $|w| < 1,$ so this is good for a disc around $z_0.$

On the other hand, we can factor out $w$ from the denominator to get

$$ \frac{1}{(w(1+\frac{i}{w}))^{2}} = \frac{1}{w^2} \frac{1}{(1 + \frac{i}{w})^2} = \frac{1}{w^2} \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \binom{-2}{n} \left ( \frac{i}{w} \right ) ^n = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \binom{-2}{n} i^n \frac{1}{w^{n+2}}, $$

where $|\frac{i}{w}| < 1$ when $|w| > 1,$ so this is good for an annulus where $|z - z_0| > 1.$

4. Translate back to $z$ land

We substituted $w = z - z_0$ earlier, so we need to substitute that back into our series and then we're done. We have to be sure to keep track of which series converges for which region.